Clamping pressure has gotten complicated with all the conflicting advice flying around. As someone who crushed more than a few joints before learning better, I learned everything there is to know about finding the right pressure. Here’s the truth: more isn’t better, and understanding why will improve every glue-up you do.

What Pressure Actually Does

Clamp pressure serves several purposes. It brings mating surfaces into intimate contact, eliminating gaps or high spots. It squeezes out excess glue, leaving a thin, optimal line. And it holds parts in position while adhesive cures.

The goal is a glue line about 0.002 to 0.006 inches thick. Thinner isn’t better—too-thin lines lack adhesive mass to fully bond. Thicker suggests insufficient pressure or poorly fitted joints.

Signs of Too Much Pressure

If you see glue squeezing out like water from a sponge, running in streams rather than beading, you’re approaching too much. Some squeeze-out is desirable; it confirms adequate coverage. But excessive squeeze-out means you’re forcing glue out of the joint.

Another warning: board cupping or bowing under clamp pressure. Wood compresses slightly under force, and excessive clamping distorts boards. When you remove clamps, the wood springs back, but glue has already set in the deformed position. The result is built-in stress.

Starved joints appear when you examine a failed glue-up. Surfaces show wood, not dried glue, meaning there wasn’t enough adhesive after excess was forced out. This looks different from adhesive failure where dried glue remains.

The Right Amount of Pressure

That’s what makes clamping tricky for us woodworkers—modern glues require only 100 to 250 PSI depending on species density. A typical parallel-jaw clamp generates 400 to 600 PSI at full tightening. You rarely need maximum.

For most furniture-scale joints, tighten until you see a thin bead of squeeze-out along the line. Then stop. Additional tightening doesn’t improve the bond and risks problems described above.

Distribution Matters More Than Magnitude

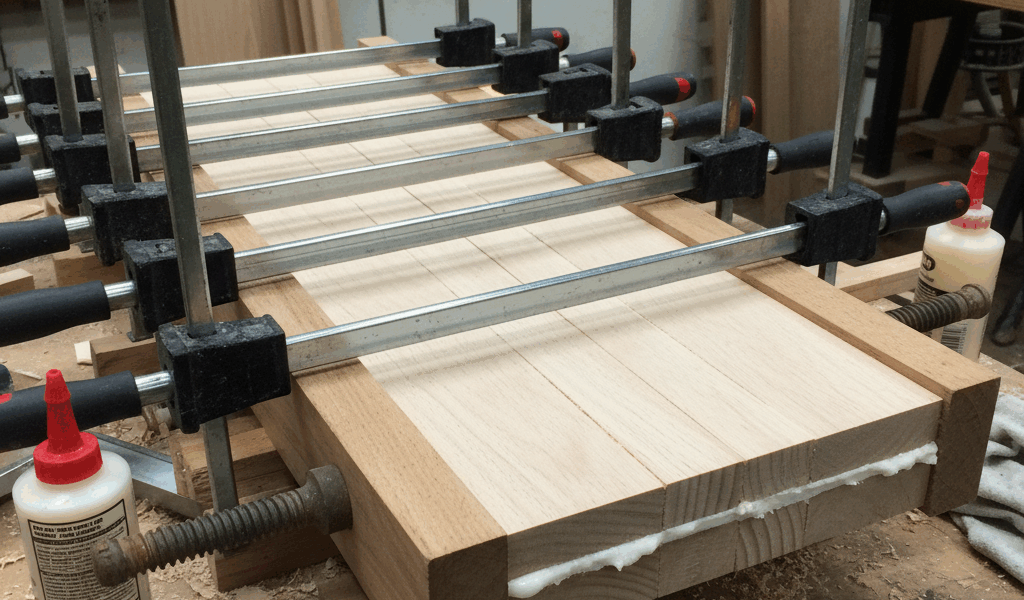

Even, well-distributed pressure produces better results than concentrated maximum pressure. Space clamps every 6-8 inches along edge joints. Use cauls—flat boards spanning the clamps—to spread pressure evenly across panel faces.

Check for gaps along the joint after initial clamping. If gaps appear between clamps, add more clamps rather than tightening existing ones. The problem is distribution, not magnitude.

Species Considerations

Softwoods and low-density hardwoods compress more easily and tolerate less pressure. Pine, cedar, and basswood can permanently dent under clamp pads. Use wider cauls and lighter pressure.

Dense tropical hardwoods require more pressure to close joints, but their compression resistance means less damage risk. Still, adequate beats maximum.

Open vs. Closed Grain

Open-grain species like oak and ash absorb more glue into pores. They need slightly more application and benefit from a brief rest before clamping. This lets pores fill before pressure closes the joint.

Closed-grain species like maple and cherry hold glue on the surface longer. They can be clamped immediately without starvation risk.

Assembly Timing

Apply pressure before glue begins to skin over. That initial tackiness signals curing has started. Clamping after this point disturbs the process and weakens the bond.

Work efficiently during assembly, but don’t rush to misalignment. A well-fitted joint with appropriate glue and moderate, evenly distributed pressure will be stronger than a rushed joint crushed into submission with maximum force.